The “negro was here to stay,” Smalls thundered, “and it was to the interests of the white man to see that he got all of his rights.” He supported his argument with data: tables and figures designed to demonstrate the economic and political clout of his state’s 600,000 black citizens (a slight majority of a total population of 1.1 million). When he rose to speak at the State Capitol in Columbia, the chamber fell silent.

Although Smalls had learned to read only in adulthood, he was a feared debater, and at age 56 the burly war hero remained an imposing figure. In 1895, he was once again a delegate to the state constitutional convention-except this time, he was hoping to defend the freedmen’s right to vote against efforts by white South Carolina Democrats to quash it. Over the next three decades, Smalls served South Carolina in both houses of its legislature and in the U.S.

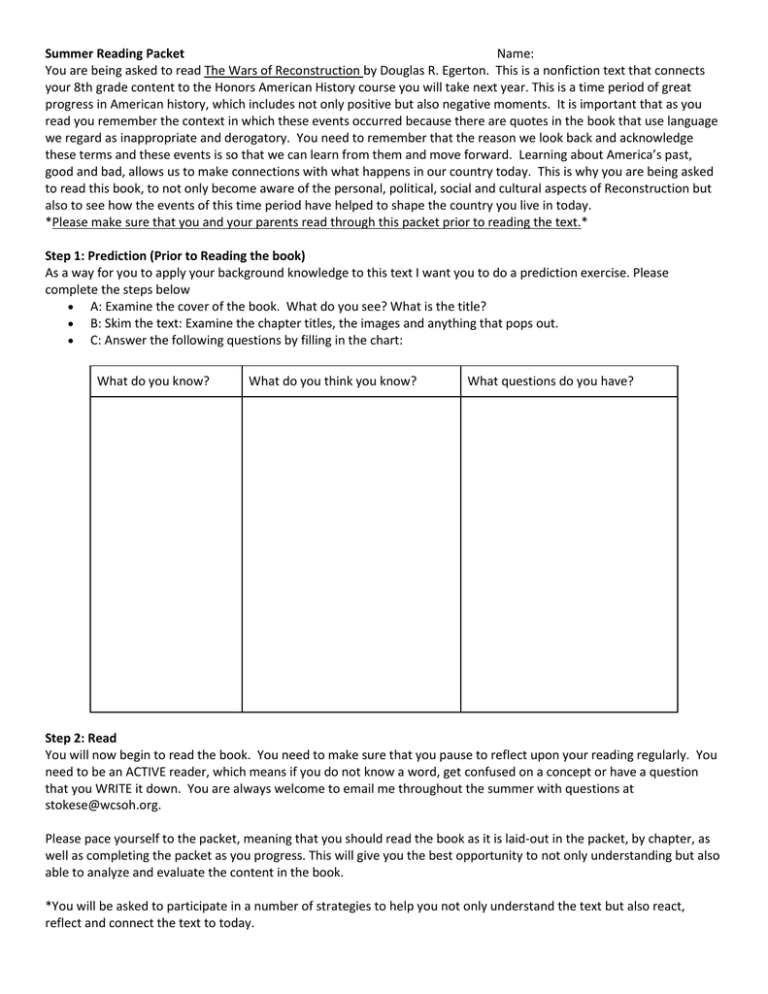

The Wars of Reconstruction: The Brief, Violent History of America's Most Progressive Eraīy 1870, just five years after Confederate surrender and thirteen years after the Dred Scott decision ruled blacks ineligible for citizenship, Congressional action had ended slavery and given the vote to black men. In 1868, he was a delegate to the South Carolina convention charged with writing a new state constitution, which guaranteed freedmen the right to vote and their children the promise of free public education. He soon dived into politics as a loyal Republican. In all, he delivered 16 enslaved persons to freedom.Īfter serving the Union cause as a pilot for the rest of the Civil War, he returned to South Carolina, opened a general store that catered to the needs of freedmen, bought his deceased master’s mansion in Beaufort and edited the Beaufort Southern Standard. Flying the South Carolina state flag and the Stars and Bars, he steered past several armed Confederate checkpoints and out to the open sea, where he exchanged his two flags for a simple white one-a gesture of surrender to a Union ship on blockade duty. On a night when the ship’s three white officers defied standing orders and left the vessel in the care of its crew, all slaves, Smalls guided it out of its slip in Charleston Harbor and picked up his wife, their two young children and other crewmen’s families at a rendezvous on the Cooper River.

I n May 1862, an enslaved man named Robert Smalls won renown by stealing the Planter, the Confederate military transport on which he served as a pilot.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)